T.S. Leonard - An Essay and A Lyric Essay

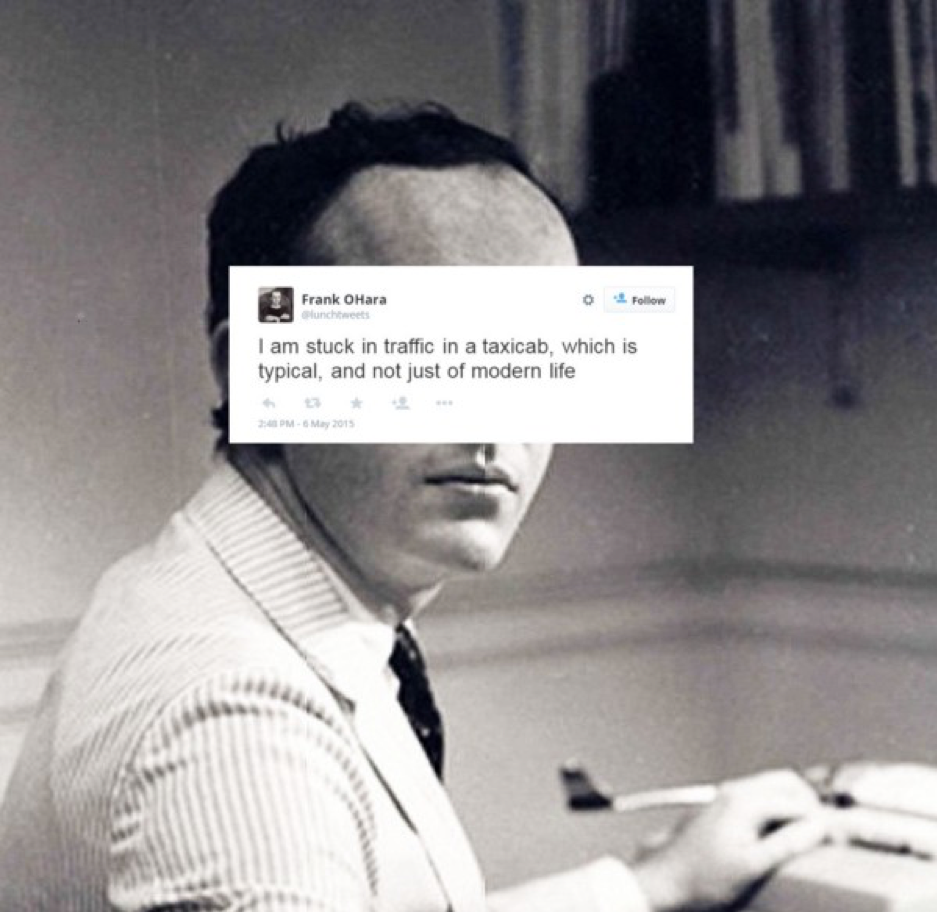

Frank O’Hara Would Have Loved Twitter.

Imagine it: New York media type, young and pretty cute, works at the MoMA. Dashes off wry observations on his lunch break: “I am stuck in traffic in a taxicab, which is typical, and not just of modern life.” Or how about, “Now I am quietly waiting for the catastrophe of my personality to seem beautiful again, and interesting, and modern.”

Yes, Frank O’Hara would have loved Twitter. Although, many dead poets might. Some living ones certainly do. Some living poets use Twitter to post their poems. Some living poets use Twitter to complain about Twitter, or some other living poets. Some living poets would rather ignore the endeavor altogether, which I fully understand, but that would be ignoring the will of the people. After all, some people credit the president’s Twitter for his political success. I don’t care much, personally, for his work: the simplistic exclamations (sad!), rampant CAPITALIZATION. But some people love the president’s words, or at least are enthralled by them, and so they choose to have them delivered instantaneously to their digital wrists.

Whether you want them to or not, the president’s words do arrive with a dizzying immediacy. But so, too, do Margaret Atwood’s (@MargaretAtwood); she has 1.94M followers. She has been recently celebrated as a coal mine canary for our regressive political reality. And so, too, do Stephen King’s (@StephenKing); he has 4.98M followers, to whom he tweets alarmingly and often about the horrors of the presidency, a behavior that eventually got him blocked by the president.

But so, too, do the words of young poets like Patricia Lockwood and Warsan Shire. Their command of the form has led to book deals and Beyoncé features. Their innovations in poetry can be delivered to your digital wrist, with as much urgency or import as the president’s rant or the novelist’s critique of him. On Twitter there’s a democracy, if you will, that makes it a fertile, frenzied space for writers — from unpublished poets to paperback millionaires.

The writer Teju Cole, when asked about Twitter, explained how it helped get the president elected: “There’s a monster that feeds on noise and we kept feeding it noise, because that was the only thing the noise machine could allow.” Teju Cole used to be on Twitter (@TejuCole, 259K followers), and his words used to be sent with dizzying immediacy to my pocket. Teju Cole was very good at Twitter, a perceptive social critic, pithy and playful with the form. His were the tweets I tried to emulate, until one day, soon after he had left the platform, I decided to quit Twitter, too.

It had occurred to me that I was having thoughts as tweets. That is to say, thoughts were occurring to me in the format of tweets, editing in real time for their possible shareability. That thought itself probably occurred as a tweet: would it be meta and absurd to tweet about quitting Twitter? I was gobbled up by the noisy beast. Every observation was suddenly being measured by its potential public reception. Would this sardonic line about supermarket sadness, I’d wonder, elicit a feverish reception from all four-hundred and fifty of my followers? It was the American Dream I was chasing: work hard, write good, get retweeted by someone at The New Yorker.

I had to quietly step away, finding other places to put my words, and sometimes forgetting that some poets and publishers were still there, carrying on. There’s the occasional yearning for what I’ve missed, like having left the room mid-conversation at a cocktail party. Since I’ve been gone, some poets I knew who were very good at Twitter have been featured in The New Yorker. One celebrity who was very loud on Twitter got elected president. And I think Frank O’Hara would have loved that. Not the president, but the possibility. The sheer ubiquity. Frank O’Hara was himself interested in immediacy, in banality, in familiar reference.

Picture it: the cute museum boy is subtweeting his crush…“Why should I share you?” he says. “Why don’t you get rid of someone else for a change?” Actually, just about every line in Meditations in an Emergency can be read like a tweet:

11:00AM: “One need never leave the confines of New York to get all the greenery one wishes — I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy, or a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life.” 4 Likes, 3 Retweets.

10:40PM: “I am the least difficult of men. All I want is boundless love.” 16 Likes, 10 Retweets.

Frank O’Hara, like any poet, dealt in images. His were often plainly stated, occurring like observations on the city street, or glossy pages in magazines. Drinking a Coke, going to the movies, cream being poured into instant coffee. His images echoed the shifting visual culture of America’s midcentury. At the time of Frank’s life, his imagery was thought by some to be shallow, like the paintings of some of his favorite pop artists. Would his Twitter reflect the current slur of constant content with as much finesse?

Those of us who have attempted to replicate Frank’s pop sensibility on the internet know writing screen interactions can be cumbersome. “I have seen the greatest minds of my generation,” I once tweeted, “fail at distilling their thoughts into 140 characters.” It got three likes. How do we write imagery in a landscape of relentless images? It’s uncharted territory, and so of course can feel clumsy to describe.

Marcel Proust, an avid art lover, while writing In Search of Lost Time drew inspiration from paintings — and the painters hanging around Belle Epoch Paris. His work reflects these images, building dimensions on the page, warping time and space. From the abstractions of color and light in the art world, Proust was inspired to elasticize time on the page. The saga often satirizes the art world, too, and — side note — Marcel Proust paid the newspaper Le Figaro 300 Francs to feature on the front page a splashy review of Swann’s Way he had penned, calling it a “little masterpiece.” Marcel Proust, maybe, would have loved Twitter.

The painters, of course, were themselves reacting to a new technology whose impact they could surely barely fathom — the camera. ”A photograph acquires something of the dignity which it ordinarily lacks,” Proust writes in Within a Budding Grove, “when it ceases to be a reproduction of reality and shows us things that no longer exist.” Proust and his painter peers were skeptical that photography promoted an emphasis on objectivity, on a fixed truth. He saw the tempting potential, though, in its power to preserve.

A half-century later, Susan Sontag would famously write a great deal about photography, and the unique power of images, at a time when America was first seeing itself — at the movies or on TV — on the screen. In her celebrated On Photography, Sontag wrote: “the camera makes real what one is experiencing…[it’s] a way of certifying experience…converting experience into an image, a souvenir.” Can you imagine what she’d have to say about Instagram? (an alternative title for this section might be Susan Sontag Would Have Hated Instagram)

Social media, in its warping refractions of how we see ourselves, is like the camera. And as we have become increasingly equipped with the ability to photograph in our pocket, we are completely captivated by the power to capture. What we choose to archive digitally is a reflection of our most basic photographic instincts: vacation slideshows (proof); flattering self-portraiture (pride); the progress of our kids and dogs (timekeeping). The striking difference is the capacity for manipulation — our images can be immediately assessed, edited, discarded — and the inclination to share.

Photography, as Sontag argued, allured with its impulse to document. Social media, additionally, creates a new compulsion to present. It invents an external memory bank where we can show and store all our tiny acts of existence. Its immediacy conditions a certain vulnerability, an effort toward — to borrow a photography term — exposure. What’s prized is what feels true. Not the truth, specifically. It’s not important that an image or expression might be thoroughly edited or plainly false; what matters is that someone chose to express it, that it documents their truth.

Contemporary characters cannot live exempt from this motivation. Mrs. Dalloway today would be concerned not just with getting the flowers herself, but also with ensuring their photogenic presentation. She would be preoccupied, one presumes, with how this dinner looked. What if someone posts a picture of their meal? We are all gripped by this dual desire to preserve and perform. We have become images, reflected and repeated, composites of all our constructed characters.

Everyone’s doing it, crafting a voice and style, developing a character through carefully chosen images and references. The internet is filthy with authors, and not just the kind who write. It’s appropriate we refer to social media outlets as platforms; it is from them we are constantly posed, delivering a performance. Social media is as likely to be the impetus for action as it is the vessel, both the kindling and the cold. “Do it for the…” post, they say. We are living for something to document. We are building an archive of proof.

Through social media, we’ve defined an artfulness in the act of sharing. Teju Cole — who, since quitting Twitter, has been writing about photography for the New York Times — is on Instagram. He has used the platform to pursue a few different experiments; for a while, he just reposted people’s selfies with the Mona Lisa.

Lately, Cole has been posting close-up shots of abstract paintings. The details sometimes show textured canvas grooves or engaging color moments, but mostly, they’re monolithic rectangles. Occasionally, Cole attaches a caption, sometimes a thoughtful poem, his or someone else’s. With one, he wrote “a photograph of a detail of a painting is a photograph, not a detail of a painting.” It’s an assertion of ownership, and a nod to the intention present even in this straightforward presentation.

We become so used to the vulnerability of performances, and we feel compelled to share. Acts of emotional exhibition that would have previously felt like a risk for alienation have become a means of connection. All sorts of people, evidently, are gripped by neurotic overthinking and deep self-scrutiny, and not just poets. The more access we’re given, the more we take it for granted.

It’s a reflection of our relationship to screens in general. Like the camera did for images, the internet has created for information a thrilling immediacy. There’s no experience to which we feel unprivileged, no story that couldn’t be told, that can’t be read. The whole of history can be nestled in a browser tab next to today’s headlines.

Carrying around a pocket atlas of information, every piece of reference comes with an implied footnote. This means that we as writers can introduce concepts or build upon ideas with a greater freedom. To wax esoteric is no longer a risk to accessibility; the reader’s access means that we should not effort to outsmart, but instead crack open windows through which the audience can crawl, investigate independently, find greater context for our voice.

I work with elementary age children, and every day I’m reminded they are, in no material sense, less intelligent than I am. If they don’t know something (yet), they how to look it up. A fifth grader told me recently he planned to write a “nostalgia column” for the the school paper. “It’ll be the 60s, the 70s, the 80s, the 90s,” he said. “Like, pop culture every 90s kid should know. Like one of those awful Buzzfeed lists,” he continued, sounding as much like a friend at brunch as someone born the year Barack Obama was elected president.

But why wouldn’t his experience of history be as panoramic and rootless? Our timeline is defined by its inevitable self-awareness: we grow increasingly nostalgic for pasts so recent they’re present. This turn toward historical awareness encourages literature that flirts with temporal fluidity.

Our contemporary world comes at us fast and formless, and it’s against the contexts of past precedents that we attempt to understand it. We shore up primary documents in personal essays, collecting and keeping as many first-person testimonies to what it has meant to live in our present moment.

It’s appropriate that new novels borrow heavily from the internet-adjusted style of the personal essay to contextualize their narratives. One of the biggest debuts of the summer, Tommy Orange’s There There, opens with a mosaic meditation on cultural representations of Native Americans. Andrew Durbin’s MacArthur Park begins with a piece about Hurricane Sandy and climate change, then throughout takes leisurely breaks from the narrative for essays on cults and contemporary artists.

What’s important to remember is that just as how we choose to represent ourselves on social media, there’s a vulnerability and an artistry to how we curate in our literature, where we choose to guide the reader. Which windows we push open. The piecework tapestries of contemporary fiction can guide across time and place, like an internet browser, and unlock a wider window of what it means to be a human now.

What would Frank O’Hara say about Twitter? Probably just “I am stuck in traffic in a taxicab, which is typical, and not just of modern life.” I mean honestly, he would have been a natural. The rapid barrage of screens does not necessarily have to compromise our capacity for artful reflection. On the contrary, this sudden overexposure is fertile ground for our most literary tendencies. For was it not in the elegance of minutiae that Frank — or Virginia or Marcel — found their greatest inspiration? And is it not from the elegance of minutiae that Twitter draws its most poetic potential? It’s the mindless encounters, the raw thoughts, made artful by the act of sharing. Our most interior preoccupations and our private dreams are elevated to content by their sheer composition.

In John Ashbery’s introductory notes to Frank’s Collected Poems, he writes that their essence is in their openness. An openness to explore the familiar, the deeply felt. This is the coveted quality of successful social media toward which we all effort: an openness, performed or sincere, to invite the wide world in. An effort, Ashbery concludes, toward the Truth.

The Truth. That’s a slippery construct these days. A truth, maybe; may be more palatable. Some truths, perhaps, how about plural? Some truths: sprung from our Rashomon Rorschach blot, oversaturated atmosphere of perspectives — collective truths. Some truths, briskly passing by, observed and unexplored, like lives on the New York City sidewalk. Who needs 14th Street, Frank? Everyone’s on their phones anyway, looking for something. The same thing?

Some truths, like some poets and some presidents, swiftly blinking by, across the screen you’re staring at in the crowded train car. The last time I was on a New York subway Mollie said, “do you ever want to just shout at everyone: hey, look up! What are we doing?” Sure, I figured. Someone’s gotta do it.

Some poet has got to grab at the elasticity, bend our shifting canvas, stretch it into something beautiful. Some poets ought to celebrate the erosions of hierarchy; while they’re at it, some poets ought to elegize. Some truths, like some poets, can stand being passed around screens, can stand being brief. Some truths and some poets take more time to get vulnerable. They’re quietly waiting to be documented.

Sure, at its worst, social media preferences loud voices and disingenuous perfectionism. It threatens nuance and encourages combative dogmatism. It makes unscrupulous men into presidents. But! In between all that noise machine static is all of us — sharing, laughing, lapping up the seductive possibilities of being so porous. It is within our power as authors to make something beautiful from our catastrophic personalities. Believe wildly that together we’re building it: a history, a celebration.

A Small Thing but My Own

In the beginning, we were gods. We turned on a spotlight and called it the sun. We shook our hips and named this dance thunder. We had this wonderful little place at the top of a mountain; from there, we created everything. We were the creators. We didn’t worry about money, because we didn’t have any. Our only currency was beauty, and beauty was ours to determine. We were gods, you say—and this is my favorite part—because we believed ourselves to be.

Again! Again! I clap. So you sigh and you yawn and you say, even little gods need lots of rest, but you start from the beginning. You tell me the story, again and again, that what we were meant to do was imagine. In the beginning, you say, we were gods. Like any story or lie, you repeated it so many times it became true.

You could have used any word then to tell me where we’d come from. Other fathers have said sissy, said pansy or queer. Other fathers have said screaming queen, as though what made the royalty embarrassing was that it announced itself. Other fathers say faggot or, simply, fag. But you said gods. You said that what gods did was create, and so like any story or lie told by a father to his son, that was the first thing I believed.

Again! Again! you clap. And so I do my best impression of a father and tell my older lover the story of how we were gods.

The night before we met, I was in a ride share with a dancer named Leslie. She was threateningly tall even with her shoes on her lap. She was explaining the different phases of her hair, how she used to be a stylist, how she used to be a blonde. I chimed in that I had been recently noticing my receding hairline. “All men,” she announced with earned certainty, “lose their hair or their hard-on. It’s either, not neither.”

I am telling you this story now because before my father was thirty, he was bald. Because before my father was your age, he was dead. I am telling you this story now because before my father was dead, he was a god. Because I think you are one of us, too—the creators. I am telling you this story now because you have to believe that before you, I was my own.

⚯

I was boy before I was body: small specks on a sonogram, arranged gender anagram. It’s a boy, they smiled under pastel blue. So the walls would be painted accordingly, so the futures would be imagined: a boy becomes a man, a son becomes a father. His life’s work will be his sturdiness. I was boy and I was body, I was soft and porous in the painted blue; I wonder if I fell in love then with the smell of paint, with its powers to transform.

What would boy be if he were orange? Distinctive but strikingly unique. Orange is bold and blinding; its sensitivity is glimpsed only in its attachments to finality: smell of death, leaves of autumn. At dawn, orange is a promise. By dusk, it is a reckoning. Orange is the memory of something that passed too fast to hold.

I told you that I never know how to title something, and you shrugged. “Titles are not more important,” you said. But is there not a godly power in the act of naming? “Maybe it should not have a title,” you suggested, “and everyone else gets to call it what they see fit.” I wanted to believe in your ability to trust and to release. I wished to scrub myself nameless and be redefined by you.

Soon after I had been declared a boy, I was given this name Francis. It was my father’s father’s name, although of course he went by Frank. And Frank was what was expected of me, too: if I were to be both boy and Francis, I would have to be Frank. In private letters I would write to myself, I signed a cursive Francis; I delighted in its delicacy. When I sign a painting I just use blocky initials. There is still something private about cursive Francis that must be kept.

Of course, when I give you a painting, I sign it Francis. I tell you it is as yet untitled, and look forward to hearing what you’ll think to name it. It is heavy strokes of indigo dancing around a golden field. It is supposed to look like the beginning of something, of us. If you ever do name this painting, you forget or fail to tell me.

⚯

It is the distinct privilege of boy that he is allowed to forget, that he may spread his legs across any sidewalk considering only himself. Sometimes I forget to forget, and my presence in this body feels disingenuous, unearned. In parking garages at night, on deserted pathways in the park, I offer an apologetic half-smile meant to convey I mean no harm. But a boy is expected to forget: to remember is an unaffordable frailty, an invitation to corruptible softness. A boy is expected to be hard.

You can smash the memory like a mirror but it will only break apart into smaller, sharper shards. You catch yourself in these unswept reflections, or they catch you. It must have been your birthday because we were standing near that fountain, the one you love where the water is coming out of the stone boy like a urine stream, and because we were talking about years. I said, “sometimes I wish I had met you twenty years ago,” and you said, “when you were five?” We laughed but I don’t remember if it was for the same reason.

I made many calculations in the first weeks after you: how old you will be once I am your age, how much life you had lived when I was still young. Eventually, these exercises seemed ridiculous, as they were each tracking the same truth—we had each other when we did, and we’re both growing from there. This is no great romance, you remind me. I scrunch my face but the video gives out—poor connection. You can only hear my quiet resignation. But that doesn’t mean it’s not a great love, you add.

Again! Again! you clap. And so we start from the beginning.

There’s a Japanese folktale in which a fisherman is taken by a turtle to an underwater palace where a princess gives him a box, and a stern warning not to open it. He returns to his village after what he thinks has been a few days to find that everyone he knew is dead; his home has vanished. He opens the box against the princess’s instruction, and it releases a cloud of white smoke, turning him into an old man.

I ask you about this fable because I’m not sure what its moral is. You advise, in typical fashion, that it’s very American for me to assume there must be a moral. But if it’s not a moral, then at least there’s a point. After the man has already returned to find that he has traveled through time—or, that everyone has time traveled without him—is his sudden aging really such a worse fate? To me, this seems an act of mercy. Ah, you sigh, but you are young. Sure, I agree, but you are not that old.

The truth is if I could open a box that would catch me up to you, I think I would. Anything to close this gap among gaps between us.

⚯

In Missouri all of our fisherman fables come from Mark Twain. We are expected to see in Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn a respectable boyishness: rascally and gruff, brave and unconcerned with consequences. We ask boys to read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in the hopes it will instill some altruism into their already hardening masculinity; they will stay for the pranks and get a sneaky dose of virtue in the process.

I knew I wanted nothing to do with caves or pranks or really even adventure, but I was enthralled by the companionship. The intimacy of Jim and Huck, out on the muddy river, alone but for the stars. The shared dreams of freedom—fleeting, impossible imagination—from the implication of one’s skin, or one’s age; from fatherlessness. This is no great romance, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a great love.

I try to describe my home to you in a way that eschews it obvious deficiencies. You say you want to see it someday, and because you love one of its prodigal sons, I believe that you do. So I tell you about the deafening sound of summer cicadas and the sudden bursts of dogwood blooms after months of being too cold to believe in spring and the brown, brown river. In our version of the fisherman’s tale, Huck comes home from the river to find everything is pretty much as he left it, and he can’t wait to leave again. All American fairy tales should have morals of release.

When we talk about The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, you keep referencing their canoe. I didn’t realize there was a different connotation in England. Either way, I say, their vessel is a raft.

I consider the word canoe, how unexpectedly it softens what looks like a firm no into a more delicate new. Would it be any easier if the problems of my structure were simply lingual? If the challenge of boy was merely its imprecision when held in the tongue? Maybe the trouble starts in trying to title a piece that is best left up for interpretation, for reinterpretation. If only the word boy could be turned over and around until it sounded more like new.

⚯