Tyler Meese - A Story

Lola in Space

1

Lola stands in the cockpit’s doorway and watches the machine flick breakers from on to off. With its plastic-coated pincer arm, the machine powers down the spacecraft’s non-essential functions. Click. Air fresheners cease to mist. Click. Lights die. The black interior of SS-MF-37 sounds how it has sounded since Lola boarded and the ship exited Earth’s atmosphere: the hull hums as it passes through gas, the carbon monoxide meter beeps a signal that Lola’s lungs are safe, her breaths rush in then out. Lola rubs her shaved head and hears the follicles crunch. Her thigh is sore but not that sore. She prods where the needle entered. The skin is tender, but that’s it; a big ant’s bite would hurt worse. She could walk, if she had anywhere to go. She knows the floor plan by counted footsteps, in feet and in meters. She closes her eyes and the ship is no darker than it was before. She opens them again and everything remains nothing. She always knew it would end like this. This is how Stasis always ends.

Lola walks backward, toe to hell, away from the cockpit, away from the flicking machine. The ringed hallway is no different in darkness. She drags her middle finger’s tip along the cold and rough metal, imagines she’s leaving behind some biological scrap as a sign that she was here, that she occupied and maintained SS-MF-37 until her end, as best she could. Whatever comes next, she has no control over. Endings are always dramatic, she thinks, and she feels dramatic. “Everything,” she says “to some degree,” out loud to no one “is decided before we start.”

The assignment was to be six months, her first of possibly many, a probationary training job. All she had to do was live aboard the ship, check done boxes on the daily task app, and not disturb the dear and mysterious cargo that was to be delivered to a space station way away from Earth. Her job was almost over.

Lola pretends that the ship is Jare’s Camry and that it is before she had left Earth, before this job, before the war had moved from surface to space. The car is aimed for his dorm’s parking lot. Soon she will take two steps at a time up the flights of stairs to her makeshift bed of piled bean bags. They just passed the green Climax, MI sign, still laughing, and she knows there is enough time to get through one more album. The Crucifucks or maybe Total Recall. All she has to do is pick which burned CD will orchestrate their drive, light cigarettes, and sing along. Lola imagines looking out on Michigan’s flat gray and the short trees with no leaves and the long straight highway.

In the dark, Lola hears the machine click off another breaker. The covers on the ship’s only windows rise and she can see the pinpricks of stars outside. Before she’d blasted off, one of the Space Taskforce 4 engineers told Lola that the two windows were locked to keep her safe, that the ship would be close enough to the sun that the rays could, at best, burn her retinas and, at worst, blind her. Radiation, he said. She’s going to die anyway, she thinks, and goes to one of the windows. She doesn’t see the sun. She doesn’t see a planet. She doesn’t really know where she is. It’s all just space to her.

As she looks out on the nothing, one green beam shoots past the ship. Then another. Then a barrage of green beams. Lola can’t see where SS-MF-37 heads directly—the windows are on the most port and starboard points of the ship—but it doesn’t matter. A galactic battlefield spreads so far that Lola can see Mecha combat units—the Red, Black, and Blue of Allied Earth and the Dual Gray of the Collected Colonies Confederation— on the portside and, after running around the darkness of the ringed hallway, on the starboard side. The giant robots aren’t firing at her spacecraft but stray energy shots shoot in Lola’s direction.

SS-MF-37 floats closer to the combat. Lola watches one Mecha charge another, fire a single green beam into the enemy robot’s head. Lola knows that inside each of the giant robots is a real human. If the cockpit is located in the head, that human is dead. If not, they’ll die shortly, oxygen seeping out of the broken husk. She watches a metal arm float away from a metal body, tethered only by tubing until the tubing snaps and liquid spurts into empty space. She watches the battle and wonders how long until SS-MF-37 is devoured by the deluge.

2

Lola woke, rubbed her eyes, and tied her long, green hair into a loose bun. The instant coffee dissolved into the boiled water, her body and mind moved, and the job placement website, again, told her to apply for transportation jobs. All that existed in Lola’s occupational future was transportation. Because she had lost her last job and had applied for Allied Earth Front’s Unemployment Insurance and had received benefits, she was required to use their job placement board. She could look elsewhere, but she had to at least make an effort with what AEF deemed her most employable skills. Because Lola’s resume listed her work with Meals on Wheels, two years of driving around Battle Creek and Kalamazoo and all the smaller cities and towns in the area, she was stamped transportation applicable. There was a war in space being fought with giant robots that demanded recourses, supplies, and humans to move from one place to another for processing, assembly, and finally blasting out of the atmosphere. Transportation jobs were always in demand.

What was not in demand was co-operatively owned grocery stores. When People’s Food Co-Op closed after forty years of service, Lola intended to use the unemployment insurance to find more fulfilling work. She disagreed with Allied Earth Front’s opinion: she was decidedly not transportation applicable.

Lola had experience managing a small crew. And maintaining inventories. And volunteering at a kids’ museum. She’d put out a Xeroxed, and later a risographed, zine, Midwest Punk Matters, for almost a decade. She’d designed menus for a bird themed pizzeria and brochures for Habitat for Humanity. These skills didn’t translate to the AEF’s job placement website’s gray boxes, to their starting dates and ending dates, to their ‘why were you terminated?’ questionnaire. When Lola broke the last ten years of her life into chunks of food service employment, her confidence faded. She wasn’t ashamed of how she survived but she was so much more than forty plus hours a week in a kitchen or at a deli counter. How could Lola convince the Allied Earth Front of her abilities when their gray boxes didn’t allow for the nuance of her life?

Lola clicked a link to an 18 wheeler licensing academy that would reward her with a commercial driver’s license, a sixty-hour work week, and the opportunity to travel all of the Western Half. The more she scrolled through the list of AEF applicable jobs, the more her balloon of hope deflated. She felt she was destined for nothing other than transportation in service of the Allied Earth Front. She would help move goods and continue the effort against the Collected Colonies Confederation and singlehandedly save all of Earth’s population from being enslaved or totally destructed. Her transportation would end the war.

Maybe Lola was just another body meant to assist in the abhorrent and endless war she barely followed but couldn’t avoid. It was the constant hum in her head as she shoved all her green hair into a beanie and stuffed limbs into a parka and walked out to Michigan’s winter of gray-crusted street snow. The winters had been more extreme in recent years, this one being the worst. Her frozen eyes found war wherever she looked: a teenager jaywalked when traffic lulled, wore a Red, Black, and Blue camo track suit, a bomber jacket with Allied stitched across the shoulders; on the sidewalk, crusted with salt and grime was a folded Colonies phone calling card; the green spray paint on the wall, bastardized Fear lyrics, read it already started on earth! space will be just as easy!

She shouldered into the convenience store and plucked a bottle of Mountain Dew from the wall of refrigerators. The one green vice she allowed herself on her fixed income. There was a TV by the register and the cashier watched some news outlet’s all hours coverage of everything war. An interview with a Mecha pilot played and the AEF service member said they were making headway, shouted an I Love You to his Wife in Flint, their two Dobermans. His fingers made a victorious V. He was so young. Lola swiped her credit card and pointed at the TV and said, “he’s dead.” The cashier, a black man in his 20-somethings, nodded and held out a receipt. “I guess,” he said.

Back in her apartment, Lola straightened throw pillows and dragged the sole of her boot around a rug, gathered up the clumped and rolled green hairball. The space was small, comfortable, and Lola felt it a necessity to keep it neat. Her bed took up most of her bedroom and she spent more of her time in the living room, on her paisley loveseat or at her computer station. She sat down at the machine and moved the mouse to wake it up.

Stasis was simple. The gameplay was all systems management. With mouse clicks you assured the spacecraft stayed operational and your avatar stayed alive for as long as possible. One new ship layout was uploaded daily and the player’s only job was to deal with the randomly generated hazards that threatened the ship. The game’s loading screen read: “Everything, to some degree, is decided before we start.” The text floated and swelled as the game mechanics set up.

Lola’s avatar, her green hair pixelated on screen, ran from room to room wherever Lola clicked. With keyboard commands and constant monitoring, Lola dove into menus and checked her ship’s systems, subsystems, and micro-processing units. She maintained oxygen levels in occupied rooms. She locked certain interior doors. She opened bay doors and let the unbreathable air of space suffocate procedurally generated intruders, while protecting herself. Once their bodies lay motionless, she closed the bay doors, restored oxygen levels, and input instruction for her ship’s AI staff to clear the corpses.

Games typically lasted from five to 45 minutes. Scores were logged and stored. The longer you lasted, the better your score, essentially, but there were other factors for how well your avatar dealt with scenarios. When Lola neared the end of her run—her ship bombarded by green enemy ion beams and her avatar’s brain controlled by an alien infection, causing her to self-sabotage the spacecraft she was meant to keep intact—she got a text from Jare saying he was outside. She finished her game, it only took a few more minutes, and she watched as her ship exploded into fiery bits that fizzled then drifted away until the screen was black. This was how Stasis always ended. A number, this time 64, appeared to let Lola know her placement out of every Allied Earth Front player so far in the day. 64 was good, but she knew there were still hours left in the 24-hour cycle for her rank to fall. Still, she had sunk hours into Stasis for those placement numbers. She shut down the game and went downstairs to let Jare in.

Jare wore a gray denim jacket over a zip up hoodie and a thick scarf wrapped around his head and neck. He had gloves with the finger tips cut off and threw his cigarette into the snow when Lola came to the door. Jare held out a plastic-wrapped egg sandwich and wrapped his arms around Lola. His smoke stink was strong but expected, and in that expectancy was wrapped a comfort. Lola breathed in.

Upstairs Jare sat at the open window and smoked another cigarette. Even though Lola had quit years ago and her lease stipulated no smoking, Lola liked to let Jare do what he wanted. “You didn’t have to bring this, you know,” she said, afghan-bundled on her loveseat, unwrapping the sandwich.

“Oh, you wouldn’t eat if I didn’t,” he said. “How’s unemployment?”

Lola caught Jare up on the excitement that was a website telling her she should drive a semitruck. Then Jare caught her up on his life. Theirs was a decade old relationship. They met when Lola ladled soup between intro studio art classes and Jare refilled plastic salad dressing bottles between education seminars. It was Western Michigan’s Bigelow dinning hall and they sat on frozen cement steps during shift breaks with shared cigarettes. Jare’s single had a pile of bean bags that became Lola’s de facto bed. First they walked home from house shows drunk off forties of Mickey’s and later Jare didn’t allow Lola to be alone. When the aunt that raised Lola had an unexpected allergic reaction and died in her car, Jare was there. Without Lola having to ask, he drove back and forth between Kalamazoo and Three Rivers so Lola could manage the intricacies of death and still make her classes.

Jare stayed in the dorms for this second year and Lola lived there while taking a semester off. The RA made threats about single occupancy meaning single occupancy, but he never followed through. Lola saved money sleeping on the bean bags but couldn’t work in the dining hall so she found a food adjacent job, utilized the ladle skills she had. Then she got her own apartment, then another food service job, then a different apartment, and another food service job. Lola always intended to pay back Jare for those months in his single, his constant chauffeuring, but she’d never found a way that felt like enough.

“Oh, you’ll find something that isn’t an 18-wheeler.” Jare dropped his butt out the window and plopped on the couch. “Tell me about Stasis.” His voice had sarcasm in it but he knew it was something that gave Lola comfort. He poked fun, but listened too.

“64th out of every other mother fucker investing time into points and clicks,” Lola said. She stood and danced with her arms, hurricaning her green hair into Jare’s face. He laughed and batted at her attack. She fell back onto the couch and they talked over sitcom reruns until Jare fell asleep and Lola took off his shoes and tucked the afghan around him before going to bed herself.

#

The next days blurred into one long span of Top Ramen, Mountain Dew, and the government’s insistence that Lola’s future was a truck with multiple trailers. She considered this future, contemplated how she could make it doable. She could listen to her We’re The Meatmen And You Suck!, she could listen to her Jan’s Rooms. She could take that truck driving job and have tattoos on her arms and legs and hands. Allied Earth Front needed bodies to carry goods and her body would be acceptable with green hair and permanent upside down crosses in her skin. She could wear a paint-stained flannel, a hat with a hook in the bill.

Jare showed up with another egg sandwich on another day and Lola asked him, “Am I a sell out if I drive transport for Allied Earth Front?”

He ashed out her window. “I don’t know what that means. Maybe those old punks were anti-government but I think the Collected Colonies Confederation wants to blow up Earth, so whatever helps.”

Jare never cared about the Michigan punk CDs Lola kept in his Camry. He listened because she needed to hear the songs, the bad recordings blared out cranked speakers. Lola’s aunt had turned her onto the stuff, showed Lola stacks of pictures from the shows she went to, the fliers she kept, recreating her favorite years in the last years of her life. She made Lola a punk and that trait was important to Lola. But so was stability and health insurance and a career of some sort. Lola knew food service but she didn’t have enough money to open her own restaurant or grocery store and either no credit or no good credit depending on which app service she used to check. The world was going to end sooner than later and Lola never wanted kids. She wanted something to put herself into, something that she could tell Jare about and he would be like “Oh, that is cool.” She had managed people and she could do so again, in a different field. It would just take time to find something.

She kept up daily with Stasis. Her placements hovered between 50th and 100th. Another day and she caught a real streak, her AI helper successfully beheaded two cyborg intruders and disposed of the bodies. When Lola thought her game was ending, she survived. Her green-haired avatar repaired the hull after a breech and replenished oxygen throughout the ship. And the game continued for another hour. When Lola did finally succumb, her ship didn’t blow up but sat in space, intact, and a large number 1 appeared over it. She had achieved the highest score for the day. There were still a few hours left within the 24-hour time frame so Lola didn’t celebrate. Not that she would celebrate Stasis, it was just what she did to unwind and she knew nothing could come of it.

What Lola didn’t know was that Stasis was more than a time killer. Space Taskforce 4, a department of Allied Earth Front’s military defense wing, monitored the official online scoreboard. It was a first screening. The next day, they would target Lola with a transportation job post that advertised spacecraft operation instead of semitruck maneuvering. She would apply with a reworked resume and cover letter that explained her transferable skills, but it wouldn’t matter: she was destined to get a video interview. She would have a bad internet connection and say “hello?” frequently and answer questions too honestly but it wouldn’t matter: she was destined to have the job offered to her. Jare would drive her to DTW and she would fly to Quinto, Ecuador, the Western Half’s largest spacecraft entry and exit point, for a week of necessary instruction. Long gone were the months of training required for space. Things would happen faster for Lola.

#

Training to maintain SS-MF-37 was more straight forward than Lola expected. The vessel’s path was pre-destined, the fuel supplies excessive, the crew a solitary Lola. The big question in her head was why. Why wouldn’t they tell her where the ship was going? Why couldn’t she know what the cargo was? She got vague answers from engineers and recruiters about dear goods and transportation and war efforts. Cargo in SS-MF-37 needed to get from Earth to a point in space for a reason no one would tell her. She didn’t know her clearance level but assumed it was low.

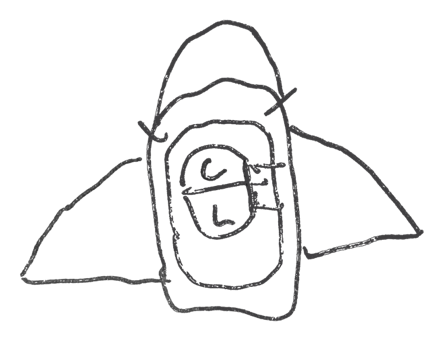

Lola’s training took place on a mock-up of the ship. An engineer drew a crude picture:

two half-circle rooms that shared a wall in the middle, one for Lola and one for the cargo, a hallway that ringed the ship, and a cockpit area where controls existed in case of an emergency, where the remotely controlled operations could be overridden.

Lola slept in her gray half-circle room, fingered buttons she would presumably never have to touch in space, and completed the daily tasks that would make up her routine. Everything was logged on a tablet, little X’s assigned to completed assignments.

The tablet had limited entertainment and was unalterable. She couldn’t add the Touch and Go discography. She couldn’t download Repo Man. There was no music or movies she liked. But the job could be important and worthwhile, she thought. There was a chance that, with this one delivery, she would be the one to stop the war. That’s what one recruiter told her. Invisible eyes had rolled in her head but she tried to lean in.

She was trying something new, something that she could do for a long time and, maybe after years of space transportation, she could die in a house with comfortable winter heating and nice summer air conditioning. She could give her time and effort and keep hidden her disagreements. She couldn’t have everything but she could maybe have something. She could see space and live on Earth and hope the population wasn’t smudged out or enslaved. At least she would help Jare; her monthly pay would be routed to his checking account.

A day of rest and a phone call on a borrowed phone and Lola told Jare “I’ll see you in a year! I love you! Don’t trash my apartment!” And he said, “Oh, you’re going to space! Poor Michiganders don’t do that! I’m popping champagne right now!” And then SS-MF-37 prepared to bust down the runway. Lola, belted secure, heaved hot air into her space suit. The engine’s bellow raced Lola’s heart in a way she didn’t expect. She was destined to die on this spacecraft, her brain told her. She begged a Space Taskforce 4 engineer to cancel the assignment. The engineer’s voice came through an ear bud and talked to her about breathing exercises. She begged the voice in her ear to call Jare and tell him to drive down to Quinto and pick her up. Instead, the voice said, “In on one and out on two.” The voice counted over and over while the ship turned and accelerated and pierced through atmospheric layers until Lola was nowhere near Earth’s surface and the connection went dead.

3

There was no true way for Lola to tell time. She didn’t know how distance traveled in space translated to hours and minutes and seconds. Geographic clues didn’t exist. Lola couldn’t point to the green Climax, MI sign and know she had twenty minutes until Jare pulled the Camry into their dorm parking lot. She couldn’t even look outside at what she imagined would be darkness with pinpricked starlight: the ship’s two windows wouldn’t open. The lights in SS-MF-37 ran on timers but Lola suspected Space Taskforce 4 controlled them remotely, could easily alter the cycle that was supposed to replicate summer’s sunshine hours. She couldn’t trust the one triangle clock for the same reason. A control tower engineer could line into the hands and pause or accelerate them.

She couldn’t trust her own body to accumulate and record the passage of time either. The dehydrated food that kept her alive and functioning was salted with a compound that inhibited keratin production. Her hair remained a shaved mat. All her green was gone, only brunette roots remained. Space Taskforce 4 explained less waste and more comfort while in space. Lola wished she had nails so she could scratch at paint and tally days. She had tried to keep track but even remembering how many days since takeoff proved difficult. She even wondered if ‘day’ was the accurate word, her not being on a planet or anything solid. Did she constitute her own planet?

The ringed hallway was Lola’s only friend. There was no contact with Space Taskforce 4. No one called in or out of SS-MF-37. She stopped checking off her tasks when she realized how pointless they were. Sweeping was out when she determined no new dust could accumulate. Where would it come from? Do human bodies make the dust of the world? Why would she spend an hour monitoring the ship’s operations when she couldn’t control them and when all she did was think about them anyway? She thought to herself, Why did I trust the government? She asked no one, out loud, “Why did I ever trust any government?” She expected none and there was no answer. If Jare were here he would have assured her that there was nothing nefarious. “Oh, wait out the ride,” he’d say. She would.

Before Lola had flown to Quinto for training, she suspected that the Allied Earth Front would reprogram her brain before sending her into space. Now she wished the procedure had been offered. If she could have been made into a True Believer, if they could have removed Doubt and installed Patriotic Software, she wouldn’t pace the ringed hallway in her Red, Black, and Blue camo sweatpants, wondering how and when she was to be fucked over and used in an unavoidable way. Her destiny was to be a tool in the endless war.

#

Lola slept and woke and ran around the ringed hallway and slept and woke and watched a sunset on her space tablet and slept and woke to a poking in her side. She imagined she was on the bean bag pile in Jare’s single. She imagined she heard his voice float into her ears, “Oh, good, you’re awake.” Except it wasn’t Jare’s voice, it wasn’t a human voice at all, just a metallic clucking. In the low sleeping light of her gray half-circle room, Lola focused on what prodded her: a plastic-coated pincer attached to a metal block body perched atop two caterpillar tracks. The body’s other arm was a large needle, which freaked Lola. If this machine were a human, the area where the face would have been was a circular screen that looked like an old tube TV with an after image burned in, which also freaked Lola. She could make out eyes and a mouth, both fluttering and blurred. Lola inched closer to the wall, further trapping herself. “□ □□□□□ □□ □□□□□□,” the machine said.

The machine lowered its claw hand and stood staring at Lola with its clouded, almost face. She assessed the situation: alone in a spacecraft with a machine she didn’t know existed that had a claw for one arm and a needle for the other. Should she put faith in her physicality and fight the thing? She had been doing the ringed hallway runs, the solitary room sit ups. The needle arm was a deterrent. She could slip past the machine and run forever circles, keep distance until the spacecraft reached its destination, let the crew there deal with it. Both options sucked to Lola.

What Lola didn’t know was this: SS-MF-37 was one of many spacecrafts shot off into the galaxy by Allied Earth Front in a desperate effort to end the war with the Collected Colonies Confederation. Her ship contained a sleeping machine that would wake as she neared the galactic battlefield and infect her with a disease as the ship plowed into enemy occupied space. The hope was that the ship would be intercepted and the disease inside her body transported to the colonies. This possibility was a stretch. Lola didn’t know that another ship identical to hers carried a hydrogen bomb. She didn’t know that yet another contained an invasive plant species. Allied Earth Front had to try everything that seemed remotely possible. The Collected Colonies Confederation wanted Earth’s resources, not the people. They were open about their aims for genocide and enslavement despite using more acceptable terms. But Lola didn’t know this. She tried to talk to the machine.

“You don’t look broken,” she said.

The machine rolled back, pivoted, and glided out of Lola’s room. “□□ □□□□ □□□□,” it said from the hallway.

For the first time, the second room’s door was open. The machine stood in the center, unlike the rest of the ship, the lights were bright. Lola could see the machine was a sloppy build. All of its internals seemed to be protected by four thick, gray metal slabs welded together. If dismemberment was Lola’s plan she would have to pry it apart with only her hands. She redirected her focus to the machine’s needle arm as it moved toward a clear plastic drum that sloshed green, stabbed into it, and sucked up the liquid.

“□□□ □□□□□□□□ □□□□□ □□□ □□□□.” The machine accelerated in Lola’s direction, then stopped, and reversed. Its blurred face kept eye contact. “□□□ □□□□□□□□ □□□□□ □□□ □□□□,” it said. There seemed to be a conflicted look in the static of its face.

This wasn’t a situation that ever happened in Stasis. There was never a surprise attack from within the spaceship. Yes, aliens could invade, either rip through the hull or transport their slimy bodies in, but they never started a journey inside the ship and lay dormant for months, then appeared and told you the damage they had planned. A burst of anger shot off inside Lola like a flare then fizzled like a dud. Does a reaction count as a decision made? What does Allied Earth Front actually have planned for me? Lola wondered. The machine nudged her with its pincer, held up its needle.

“What the fuck?” Lola said. Her hands couldn’t even make dents against the machine’s shoddy but sturdy body. If she fought she would be poked with the green-filled needle. If she didn’t fight she would be poked with the green-filled needle. She would be killed. Or maybe the green liquid was a sleeping agent for a quick ride back to Earth. Maybe that’s why the robot appeared in her room, when she was supposed to be asleep. Maybe she wasn’t about to die. Did it matter?

Lola stood and stared at the machine. The hunk of metal was the last thing she would see. Lola thought of the absurdity of her on a spaceship with a murderous machine. What did anything matter? Her only wish was for something cooler, something otherworldly like a bipedal roach that communicated in pheromones. A metal box bad at communication was a lazy end. “Fuck you,” she told the machine. She held out her arm. The machine advanced and jabbed the needle deep into her thigh. The green injection didn’t make Lola feel any different. The machine glided past and into the hallway that connected the two gray half-circle rooms and scooted in the direction of the ship’s cockpit. When Lola didn’t move, the machine came back and motioned with its now drained needle hand to follow. Lola followed.